Surfers in Ventura.

This post is for anyone who comes across my blog, but I am writing it keeping in mind that a number of Professors in Loyola’s English department will in a week or so be given a stack of senior theses, neatly typed up and printed out, and somewhere in the pile will be a single piece of paper with the URL that leads to this blog. What once was a creative diversion has become my senior thesis, and while I write for a general audience, this blog serves a dual purpose as the capstone of my college experience.

When I graduated high school, My best friend and I would go surfing every morning, riding up the PCH or the 101, parking along the road-side and paddling out at Surfer’s Point or Rincon or Solimar. Back home I have a 9’6 Weber and a 6’2 board by an Oxnard shaper named Klaus Jones, and as much as I suck at surfing, I’ve never stayed upset when I got into the water. Even on the flattest days (and California has plenty of those), bobbing like a cork in the water was a peaceful experience. Surfing is like the white-noise in California coastal life. Even for those completely immersed in it, we don’t often trouble its meaning. It is an escape, a pleasure, a challenge: play. Somehow, while quasi-landlocked in New Orleans, I ended up thinking about surfing a lot. I blame this on Roland Barthes, David Foster Wallace, and Dr. Christopher Schaberg.

Christopher Schaberg, not pictured here, but probably picturing here right now.

Barthes’ Mythologies showed how anything could be complicated. Mythologies takes objects as varied as wooden blocks and rocket-men and extrapolates what it is that we invest in those things. He unpacks the relationship between the sign and the signifier. But most importantly to me, he writes beautiful short pieces that make me reconsider everything. For one of Dr. Schaberg’s classes, each of us was assigned an article at random, on which we had to write a Barthes-type piece. Mine was based on an advertisement for Delta Airlines promoting free on-board wi-fi. What I wrote became a short piece on Airplanereading.org entitled “Expect the Internet.” Writing that piece and others like it pushed my pre-conceived notions of genre away. While I never believed that there were any strict rules concerning genre, I did not do much to push against the concept. My fiction was fiction. My essays were essays. But when you write the Barthian piece, you must simultaneously be analytical, critical, playful and artistic. You aim as much to be insightful as you do to be entertaining. And what’s more, the thing that you write about becomes simultaneously emphasized and diminished, because you show its individual importance, and in doing so, you show that everything contains this sort of importance. You could write about an armchair or a wig or a coconut or skin flakes. Anything can be exploded. And this action is important to emphasize, because the end-goal of each piece is not to come to a conclusion, but to send bits of shrapnel off in every direction, and those bits have effects wherever they land, and they are in themselves new affects.

If Barthes was the methodological framework, David Foster Wallace was the model. Everything from Infinite Jest to A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again rests atop a foundation of personal experience, critical theory, philosophy and spectacular literary pyrotechnics used to stunning effect. And in this case, what was most important to me was the fact that David Foster Wallace didn’t confine himself to genre or style. He was just a writer. Book reviews, essays, dictionary entries, anthology introductions, epic tomes, post-modern short stories, jokes, speeches, screenplays (as embedded into a footnote in Infinite Jest); Wallace was what I want to be. And what was most fascinating to me is that he found meaning, beauty, truth and sincerity in topics that would, to the average person, be considered mundane.

While surfing has particular meanings for me, what I want to emphasize is that it didn’t matter what I chose to write about. It mattered that I picked a singular idea and followed it wherever it led. For this reason, my thesis is not clean and uniform, and coming to the end will not bring about any sort of catharsis (not in its online incarnation). When you write on the Internet, you abandon some of that formality. You write faster, looser and with a different consideration of audience. And in fact, my blog is technically an online failure. It has achieved no degree of virality and no steady following. In over two years, I have gotten around 1,600 views, which amounts to just over two views per day over the two year period. You almost have to try to get that unnoticed on the internet.

But let’s look at that data in another way. The typical thesis will usually be read by the author, his or her advisor, a committee of reviewers and maybe two or three really good friends. Generously, we’re talking ten to twenty people. The Deep Water Breaks has been available to a wide audience since its inception, and while it averages out to two a day, the fact is that such an analysis isn’t telling. The viewership on my blog has actually grown. Initially, months would pass without any traffic. But since about June of 2012, the daily average has been more around fifteen, with spikes up to thirty or forty.

As websites like Buzzfeed, Upworthy, and the Huffington Post demonstrate, there is a whole social psychology to viral content, and this psychology is embedded into a concept known as click-bait. I’d love to explain click-bait, but this isn’t the time or place. I’m running out of words. Suffice to say, what I do isn’t intended to generate traffic. It’s main goal is to wrestle with ideas.

The lack of digital success for The Deep Water Breaks is not an indication that the project has been a failure. My research has led to publications in various mediums. I reviewed Krista Comer’s book Surfer Girls in the New World Order, a cultural study for feminism and globalization, for Interstitial: a Journal of Modern Culture and Events; I’ve published an essay on Apple’s new operating system OSX Mavericks, titled “Apple’s Private Beach” in The Millions, which is currently considered one of the best literary sites on the web; most recently I published a short story titled “Breaking Pierpont” at Lent Mag, a hip new literary journal run out of Ol’ Miss’s graduate MFA program. The latter was actually the first piece I wrote for the blog, but it has been taken down in anticipation of its publication.

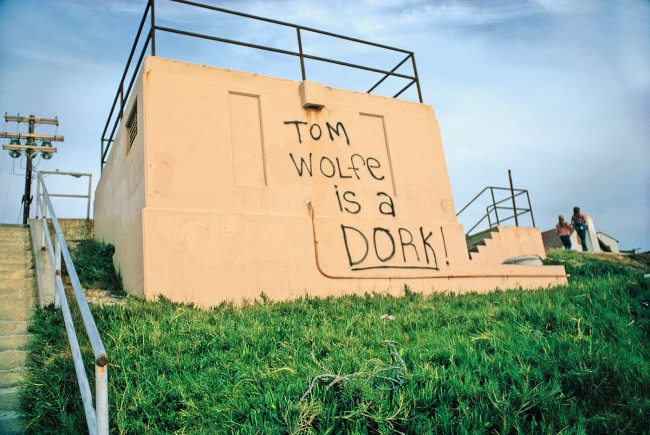

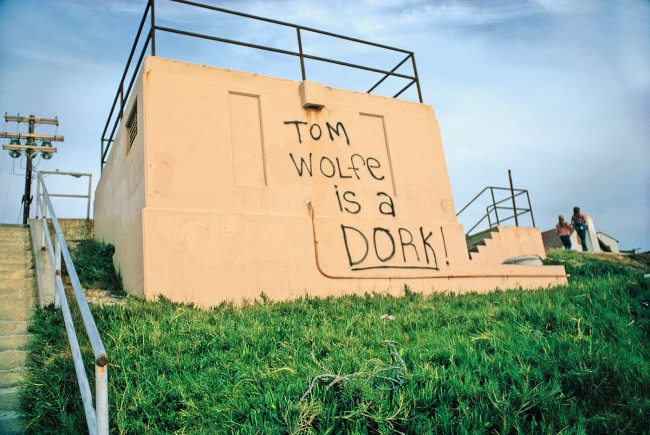

The other exciting aspect of this project is that there are very few other people doing what I am doing. Matt Warshaw and Ben Marcus have worked tirelessly to chronicle the history of surfing, capturing and preserving oral histories and rare texts. Krista Comer has worked to create room in academia for critical approaches to surfing. Novelists like Tim Winton and Kem Nunn have produced beautiful works like Breathe and Tapping the Source, while Tom Wolfe’s essay “The Pump House Gang” has elicited the ire of the very surfers he portrayed, who would love the opportunity to knock Wolfe clean out of his dapper white suit. But overall, the field is wide open to exploration, and this project has been as much about me finding work to model as it has been about setting the stage for my own literary experiments.

The Pump House in La Jolla, California

The project is far from over. As I write this, I am preparing to travel to Port Fourchon and Grand Isle, where I will view the only two surfable beaches on Louisiana’s coast, both of which have gone unsurfed since the BP oil spill. And in the long run, these pieces will join a collection of essays that I hope to publish as a book. Beyond that, the material is all working to toward a larger piece of fiction, whose form I am a long way from fully understanding.

To the readers reviewing this project: I’ve gussied up the website in order to present a more coherent narrative. Normally, a blog would be viewed in a reverse-chronological order, and most of the time the reader will simply select which pieces he or she would like to read. As you read my blog, you will be able to scroll down the page, and read the pieces starting at the top with the first piece I wrote, and continuing on until you reach the most current ones. I’ve made this change so that the reader can see how this project has changed over the course of the last two years. Further, I have made significant edits to most of the pieces, and I have removed posts that I deemed unfit or irrelevant. I wrestled with whether or not I should do any editing beyond proofing, but when I went back over the old pieces, I realized that often I didn’t fully understand what I was writing, and I had written most of those pieces in the interest of time. I have learned so much about surf-culture that it has been exciting to go back and revise from a more informed perspective. So, in effect, reading this is not so much an exploration of a preserved artifact, necessarily. But what I fought to preserve was the ideological and stylistic elements employed in each post. You will see the changes and the stumbles. You will see me learning how to stand on my board.