Boarders of Class Distinction: How Paddle Boarding has Come to Represent the Leisure-Class

photo courtesy of Ron Croci

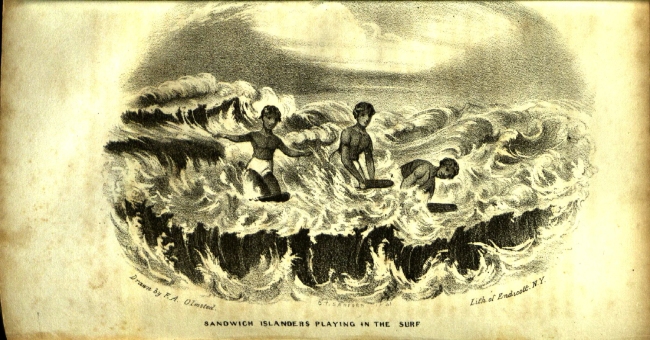

In Hawaii, the longest boards, known locally as Olo boards, were reserved for royalty. The shorter alaia were ridden by non-royals. Olo boards ranged from twelve to eighteen feet or more, and were crafted for smooth, easy rides, but this was at the sacrifice of maneuverability. Additionally, it took multiple people just to carry the board into the water. The shorter, plebeian alaia became the driving force behind the art of surfing as they were more maneuverable, easier to make, and rarely required more than one person to transport them. However, the sport was all but wiped out on the islands by Captain James Cook upon colonization. Surf-bathing was considered lewd and lascivious, and was therefore not conducive to the so-called civilizing project.

Fortunately, the sport underwent a resurgence around the turn of the 20th century, thanks to its preservation by a small number of natives. That resurgence, along with the cultural exploitation of imperialism, transported modern surfing from the Pacific islands to the rest of the world. With the globalization of the sport (and the technological thrust of post-war industry) boards became shorter, lighter, and faster.

In this way, a new sort of stratification developed: a stratification divided ostensibly by skill. From 1960 to 1980, boards transformed from hulking wooden ships to sleek, space-aged poly-urethane cruise-missiles. Anyone riding a long board post-1975 was a kook ( i.e. dweeb, dork, loser, shoobie—take your pick).

But even this began to change in the 1990’s. The hyper-competitive nature of the 80’s and 90’s led to an era of introspection, and once again, the sport changed. Long boarding was no longer passé. Surfers explored it as an art form unto itself. Now, long boarding competitions are held all over the world, sometimes alongside short board competitions. But cultures tend to replace points of contention with new prejudices, and surfers have for the last decade taken aim at the latest trend: paddle boarding.

A paddle board is a hulking thing, with a minimum length of nine feet, extending out to twelve to thirteen feet, typically wider and thicker than a surfboard. This is all meant to provide the stability to stand on the object while it floats in relatively stable waters. Like the boards ridden by Hawaiian royalty, a paddle board sacrifices maneuverability and convenience for comfort. While it’s true of some longboards, paddle boards almost dictate the use of a vehicle to move them around. Once they are in the water, the rider stands and paddles out to sea, easily getting over any moderate surf without resorting to duck-diving (where a surfer pushes his board and himself beneath the water to avoid a breaking wave). Many surfers consider the ease with which a paddle boarder gets into and beyond the line-up, and with which he or she subsequently positions and inserts him or her self into the wave (in some cases completely disregarding the other surfers in the water) as an unfair advantage. There is an additional sense of Us V. Them that arises from the economic disparity between the cost of a typical surfboard (which is by no means cheap) and that of a paddle board; a difference between a surfer’s $300 and a paddle boarder’s minimum $700. Of course, prices vary, and both can reach into the tens of thousands, but what is important here is perception. And it seems that at the moment, the perceived gap between paddle boarding and surfing is synonymous with that of the Hawaiian royals to their subjects.